III. HUMANOID ROBOT RETARGETING & CONTROL

This section describes the retargeting and control techniques for unilateral teleoperation of humanoid robots. We can define the retargeting and control as a mapping \(\mathbb{H}: A \to A^{\prime}\) where \(A\) is the domain of the perceived human actions (kinematic and dynamic trajectories) and \(A^{\prime}\) is the space of robot actions. In this definition, the mapping principle identifies the robot autonomy and the human authority in the teleoperation scenario. This mapping should be identified such that it minimizes the difference between the human intent and the robot actions while respecting the constraints in the teleoperation scenario.

Humanoid robot retargeting and control introduces many challenges to teleoperation scenarios, namely due to the nonlinear, hybrid, and underactuated dynamics of humanoids with high degrees of freedom, as well as imprecise robot dynamical model and control, and partially-known environment dynamics.

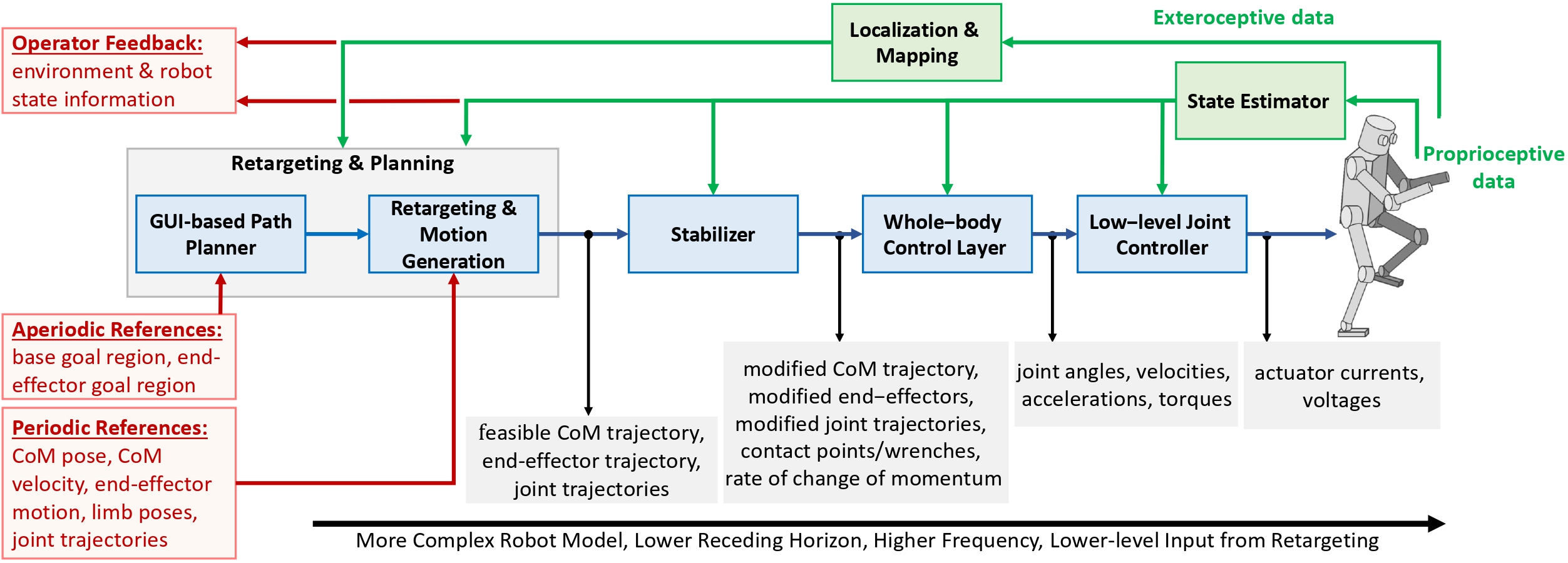

All these challenges together with the fact that the robot retargeting and controller blocks (in Fig. 3) usually run online, make the problem even more complicated.

To overcome the introduced challenges, model-based optimal control architectures are the foremost technique used in the literature.

During DRC, most of the finalist architectures converged to a similar design

A. Modeling

1) Notations and complete humanoid robot models

Most humans and humanoid robots are modeled as multi-body mechanical systems with \(n+1\) rigid bodies, called links, connected with \(n\) joints, each with one degree of freedom.

The configuration of a humanoid robot with \(n\) joints depends on the robot shape, i.e., joint angles \(\bf{s}\in \mathbb{R}^n\), the position \(^{\mathcal{I}}\bf{p}_{\mathcal{B}}\in \mathbb{R}^3\), and orientation \(^{\mathcal{I}}{\bf{R}}_{\mathcal{B}}\in SO(3)\) of the floating base (usually associated with the pelvis, \({\mathcal{B}}\)) relative to the inertial or world frame \(\mathcal{I}\)\footnote{ With the abuse of notation, we will drop \(\mathcal{I}\) in formulas for simplicity.}. The robot configuration is indicated by \(\bf{q} = (^{\mathcal{I}}\bf{p}_{\mathcal{B}}, ^{\mathcal{I}}{\bf{R}}_{\mathcal{B}}, \bf{s})\).

The pose of a frame attached to a robot link \(\mathcal{A}\) is computed via \((^{\mathcal{I}}\bf{p}_{\mathcal{A}}, ^{\mathcal{I}}\bf{R}_{\mathcal{A}}) = \bf{\mathcal{H}}_A(\bf{q})\), where \(\bf{\mathcal{H}}_A(\cdot)\) is the geometrical forward kinematics.

The velocity of the model is summarized in the

vector \(\bf{\nu}=(^{\mathcal{I}}\dot{\bf{p}}_{\mathcal{B}},^{\mathcal{I}}{\bf{\omega}}_{\mathcal{B}}, \dot{\bf{s}}) \in \mathbb{R}^{n+6}\), where \(^{\mathcal{I}}\dot{\bf{p}}_{\mathcal{B}}\), \(^{\mathcal{I}}{\bf{\omega}}_{\mathcal{B}}\) are the base linear and rotational (angular) velocity of the base frame, and \(\dot{\bf{s}}\) is the joints velocity vector of the robot.

The velocity of a frame \(\mathcal{A}\) attached to the robot, i.e., \(^{\mathcal{I}}\bf{v}_{\mathcal{A}}= (^{\mathcal{I}}\dot{\bf{p}}_{\mathcal{A}},^{\mathcal{I}}{\bf{\omega}}_{\mathcal{A}})\), is computed by Jacobian of \(\mathcal{A}\) with the linear and angular parts, therefore \(^{\mathcal{A}}\bf{v}_{\mathcal{I}}= \bf{\mathcal{J}}_A(\bf{q}) \bf{\nu}\).

Finally, the \(n+6\) robot dynamics equations, with all \(n_c\) contact forces applied on the robot, are described by

2) Simplified humanoid robot models

Various simplified models are proposed in the literature in order to extract intuitive control heuristics and for real-time lower order motion planning.

The most well-known approximation of humanoid dynamics is the inverted pendulum model

The base of the LIPM is often assumed to be the Zero Moment Point (ZMP) (equivalent to the center of pressure, CoP) of the humanoid robot

B. Retargeting and Planning

The goal of this block in Fig. 3 is to morph the human commands or measurements coming from the teleoperation devices into robot references.

It comprises the reference motions for the robot links as well as the robot locomotion references, i.e., alternate footstep locations, timings, and allocating a given footstep to the left or right foot to follow the user’s commands.

The input to this block may vary according to the task and system requirements, and consequently the design choice and retargeting policy differ.

Besides, the retargeting policy can even be determined online as a classification or regression problem using the human speech and psychophysiological state. For example in

Teleoperation devices may provide different types of input to retargeting and planning. The inputs can be i) the desired goal pose (region) in the workspace for the base and the end-effectors using GUIs (high-level), ii) the CoM velocity, the base rotational velocity, the end-effector motion, the user’s desired footstep contacts, or whole-body motion (low-level). While at a low-level, the user is in charge of the obstacle avoidance, the planning and retargeting at the high-level deals with finding the path leading to the desired goal. The output of the high-level goes to the lower level in order to finally compute the robot reference joint angles, footstep contacts and timings as the output of the block. We structured the rest of this subsection according to the input category.

1) GUI-based Path Planner

When the user provides the goal region of the robot base or arms through GUIs, the humanoid robot not only should plan its footsteps or arm motion but also should find a feasible path for reaching the goal, if any exists. Related to the footsteps, contrary to wheeled mobile robots, a feasible path here refers to an obstacle-free path or one where the humanoid robot can traverse the obstacles by stepping over. Primary approaches for solving the high-level path planning are search-based methods and reactive methods. The first step toward finding a feasible path, i.e., regions where the robot can move, is to perceive the workspace by means of the robot perception system. Following the identification of the workspace, a feasible path is planned.

Search-based algorithms try to find a path from the starting point to the goal region by searching a graph. The graph can be made using a grid map of the environment or by a random sampling of the environment.

Some of the methods used in the literature to perform footstep planning are A*

Reactive methods for high-level kinematic retargeting and path planning problems can be addressed as an optimization problem or as a dynamical system.

In

2) Retargeting and Motion Generation

Given the continuous measurements from the teleoperation devices, we can divide the retargeting approaches into three groups: lower-body footstep motion generation, upper-body retargeting, and whole-body retargeting.

Lower-body footstep motion generation:

The role of this block is to plan the footstep motion and find the sequence of foot locations and timings given the CoM position or velocity, and the floating base orientation or angular velocity provided by teleoperation devices.

One possible approach to address this problem is based on the instantaneous capture point

Upper-body retargeting:

In this method, the retargeting is done either in task space or configuration space.

In the task space retargeting, the Cartesian pose (or velocity) of some human limbs is mapped to corresponding values for the robot limbs.

Later, the inverse kinematic problem is solved by minimizing a cost function on the basis of the robot model while considering the robot constraints

Configuration space retargeting refers to the mapping in the joint space from human to robot. This morphing is normally used when the human and robot have similar joint orders.

In this technique, human measurements and model are used in an inverse kinematics problem. The joint angles and velocity of the human joints are identified and mapped to the corresponding joints of the robot

Whole-body retargeting:

This method measures the whole-body motion of human and kinematically retargets to the robot motion, similar to the upper-body retargeting approaches. Given the environment information, this approach may consider the contact constraints in the retargeting phase. Thus, this approach yields footstep locations, sequences, and timings. Later, outputs of this technique are provided to the stabilizer, to deliberate on the feasibility and enhance the robot stability

C. Stabilizer

The main goal of the stabilizer is to implement a control policy that dynamically adapt input references to enhance the stability and balance of the centroidal dynamics of the robot. Because of the complexity of robot dynamics, classical approaches are limited to examine the stability of a closed-loop control system.

Therefore, other insights such as ZMP criteria and DCM dynamics are tailored in order to evaluate how far the robot is about to fall

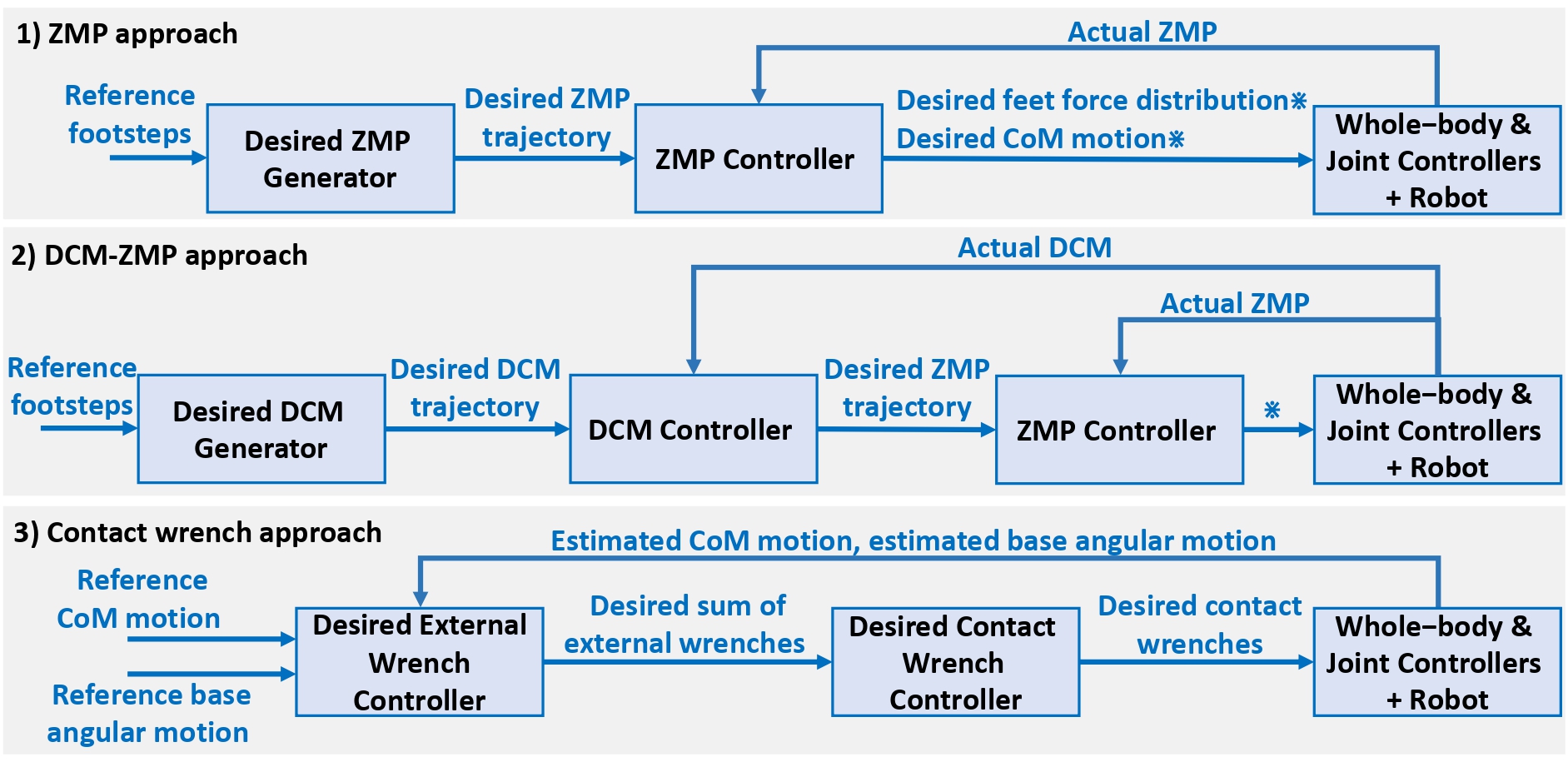

1) ZMP approach

This approach is based on the idea that the robot’s ZMP should remain inside of the support polygon of the base

2) DCM-ZMP approach

Another approach that is often employed with the simplified model retargeting and control is the DCM

3) Contact wrench approach

This approach finds the desired contact wrenches at each contact point such that it enhances the robot stability. A schematic block diagram of this controller is shown in Fig. 4.

This controller has been initially introduced in

D. Whole-Body Control Layer (WBC)

The WBC block in Fig.3 gets as input the retargeted human references corrected by the stabilizer, and provides as an output the robot joint angles, velocities, accelerations, and/or the joint torques.

The whole-body control problem can be formalized with different cost functions and be solved as a QP problem or other approaches such as Linear Quadratic Regulator (LQR)

1) Whole-body inverse instantaneous velocity kinematics control

The problem of inverse instantaneous or velocity kinematics is to find the configuration state velocity vector \(\bf{\nu}(t)\) for a given set of task space velocities using the Jacobian relation.

One common approach is to formalize the controller as a constrained QP problem with inequality and equality constraints.

Conventional solutions of redundant inverse kinematics are founded on the pseudo-inverse of the Jacobian matrix

2) Whole-body inverse kinematics control

The problem of Inverse Kinematics (IK) is to find the configuration space vector \(\bf{q}(t)\) given the reference task space poses. This problem can be sometimes solved analytically for determined robots; however, this solution is not scalable to different architectures and for a redundant humanoid robot (with a high degree of freedom), it is not feasible. Differently from inverse instantaneous velocity kinematics, to solve the IK problem a nonlinear constrained optimization problem is defined using the geometrical forward kinematics relation. Solving this problem might be time-consuming and the results can be discontinuous as well. To solve these challenges, a common approach in the literature is to transform the whole-body IK into a whole-body inverse velocity kinematics problem.

3) Whole-body inverse dynamics control

The Inverse Dynamics (ID) refers to the problem of finding the joint torques of the robot to achieve the desired motion given the robot’s constraints such as joint torque limits and feasible contacts.

There are different techniques to solve the ID problem in the literature

4) Momentum-based control

This controller finds the configuration space acceleration and ground reaction forces such that the robot follows the given desired rate of change of whole-body momentum

E. Low-level Joint Controller

One of the main challenges in deploying a humanoid robot controller is the different behavior obtained in simulation and on the real robot of the low-level joint torque tracking.

The low-level joint controller is in charge of generating motor commands to ensure the tracking of the higher-level control inputs.

The input to the joint controller can be the desired joint positions, velocities, torques, or a mixture of them. The output of this controller is the current or voltage to the motors driving the joints.

While the joint position can be directly measured by the encoder sensors, the joint velocity feedback is obtained by differentiating in time the encoder values, hence it can be noisy. Joint torque sensors or whole-body estimation algorithms equipped with distributed joint-torque sensors can estimate the generated joint torques.

The torque control of the robot joints is more challenging because of the dynamics of the joints which are subject to friction and the mechanical power transmission from the motor to the joint shaft.

On the other hand, compliance control of the joints allows for more robust locomotion and a safer interaction of the robot with the humans and the environment.

For example, ankle joint torque control allows for conforming the foot to the ground in case of small obstacles or a mismatch between the ground slope and its estimation.

However, the compliance control with only joint torques may lead to poor velocity or position tracking, therefore a mixture of them is proposed in the feedback and feed-forward terms of the joint controller in

F. State Estimator, Localization and Mapping

These blocks in Fig. 3 receive measurements from the robot sensors and estimate the necessary information for other blocks in Fig.3 or to the human as shown in Fig. 2 (for assisted teleoperation).

A family of well-known model-based estimation techniques commonly used in robotics is the Kalman filters.

The joint encoders are used to estimate the joint angles, velocities, and acceleration.

These joint states accompanied by the robot dynamics model in Eq. (1) and force/torque sensors can be used to estimate joint torques and external forces

One of the challenges specific to humanoid robots is the estimation of the robot base, and eventually robot localization in an environment.

For the estimation, either proprioceptive sensors (i.e., joint encoders and IMU sensor attached to a robot link) or a combination of proprioceptive and exteroceptive sensors (such as cameras, GPS) are employed.

When only proprioceptive sensors are used, a common approach is to assume that at each time instant at least one of the robot links is in contact with the ground, therefore the frame attached to the contact link has zero velocity and no slippage. With this assumption and taking into account the floating base frame pose in the kinematic chain, one can estimate the floating base velocity given the joint velocity vector, and eventually the base pose by integrating those velocities. However, the error of estimation is propagated over time due to kinematic modeling errors.

To enhance the accuracy and limit the uncertainty of state estimation endowed with the odometry, IMU measurements are fused in the estimation process

G. Challenges and Future Directions for Retargeting and Control

Humanoid robot teleoperation is a new field, and many challenges to put together whole-body coordinated motion retargeting, planning, stability, and control are not addressed effectively yet. For example, dividing the retargeting and planning problems of humanoid robot teleoperations appears to be useful but not effective in performing agile teleoperation tasks outside of the lab (in the real world) and in unstructured environment as it is the case for many hazardous environments and disaster response scenarios. Many of the techniques adopted so far use simplified models of humanoid robots. Although these approaches are computationally efficient, they are limiting due to the adopted simplifying assumptions, e.g., fixed robot CoM height, ignorance of human or robot rotational motion, the existence of at least one contact point with no slippage between the robot and environment.

An alternative approach to solving simultaneously whole-body coordinated retargeting and planning problems is using the MPC technique and

defining them as optimization problems with equality and inequality constraints. However, they are non-linear and non-convex optimization problems with large input and state spaces; therefore, they are computationally demanding, and the optimization may suffer from local minima.

This issue intensified when retargeting the rotational motion and angular momentum of the human to the robot, while biomechanical studies show their importance as one major underlying component of the human-like coordinated motion

While the MPC approach can be a valid solution for the humanoid robot teleoperation, it is not sufficient when deploying the robot in the real world to perform various tasks in an unstructured and dynamic environment with varying compliance and slippery characteristics. An approach to resolve these challenges is to introduce new sets of manual heuristics and constraints to the optimization problem for every scenario and environment. However, it is tedious and inefficient to generalize over different situations. To overcome these drawbacks, data-driven approaches with special attention to the robot dynamics and stability indications have shown promising results in the learning and mobile robot communities.

are some of the successful examples of leveraging neural networks and reinforcement learning (RL) techniques.

In retargeting problems, safety considerations can be explicitly enforced as well