II. TELEOPERATION SYSTEM & DEVICES

In the literature, the terms teleoperation and telexistence have been used indistinctly in different contexts. Telexistence refers to the technology that allows human to virtually exist in a remote location through an avatar, experiencing real-time sensations from the remote site

In a teleoperation setup, the user is the person who teleoperates the humanoid robot and identifies the teleoperation goal, i.e. intended outcome, through interfaces. The interfaces are the means of the interaction between the user and the robot. The nature of the exchanging information, constraints, the task requirements, and the degree of shared autonomy determine different preferences on the interface modalities, according to specific metrics which will be discussed later. Moreover, the choice of the interfaces should make the user feel comfortable, hence enabling a natural and intuitive teleoperation.

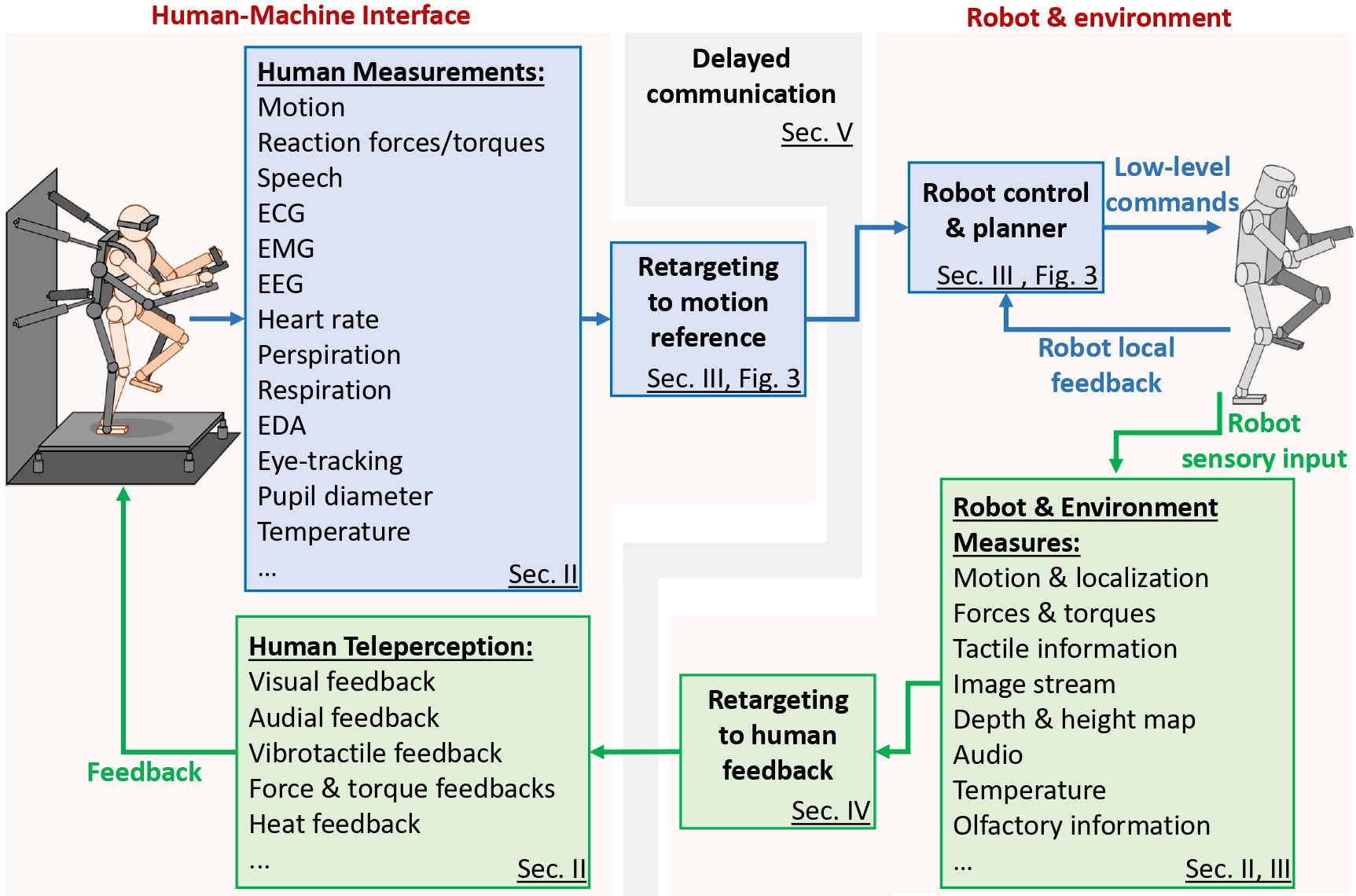

A. Teleoperation Architecture

Fig. 2 shows a schematic view of the architecture for teleoperating a humanoid robot. First, human kinematic and dynamic information are measured and transmitted to the humanoid robot motion for teleoperation. More complex retargeting methods (i.e., mapping of the human motion to the robot motion), employed in assisted teleoperation systems (Sec. IV), may need the estimation of the user reaction forces/torques. There are cases in which also physiological signals are measured in order to estimate the psychophysiological state of the user, which can help enhancing the performance of the teleoperation. On the basis of the estimated states, the retargeting policy is selected and the references are provided to the robot accordingly. Teleoperation systems are employed not only for telemanipulation scenarios but also for social teleinteractions (i.e. remotely interacting with other people). In this case, the robot’s anthropomorphic motion and social cues such as facial expressions can enhance the interaction experience. Therefore, rich human sensory information is indispensable.

To effectively teleoperate the robot, the user should make proper decisions; therefore he/she should receive various feedback from the remote environment and the robot. In many cases, the sensors for perceiving the human data and the technology to provide feedback to the user are integrated together in an interface. In the rest of the section, we will discuss different available interfaces and sensor technologies in teleoperation scenarios, whereas their design and evaluation will be discussed later in Sec. VI.

The retargeting block (Fig. 2) maps human sensory information to the reference behavior for the robot teleoperation, hence the human can be considered as master or leader, and the robot as slave or follower. We can discern two retargeting strategies: unilateral and bilateral teleoperation. In the unilateral approach, the coupling between the human and robot takes place only in one direction. The human operator can still receive haptic feedback either as a kinesthetic cue not directly related to the contact force being generated by the robot or as an indirect force in a passive part of her/his body not commanding the robot. But in bilateral systems, human and humanoid robot are directly coupled. The choice of bilateral retargeting depends on the task, communication rate, and degree of shared autonomy, as will be discussed in Sec. IV.

The human retargeted information, together with the feedback from the robot, are streamed over a communication channel that could be non-ideal. In fact, long distances between the operator and the robot or poor network conditions may induce delays in the flow of information, packet loss and limited bandwidth, adversely affecting the teleoperation experience. Sec. V details the approaches in the literature to teleoperate robots in such conditions. Finally, the robot local control loop generates the low level commands- i.e., joints position, velocity, or torque references- to the robot, taking into account the human references (Sec. III).

B. Human Sensory Measurement Devices

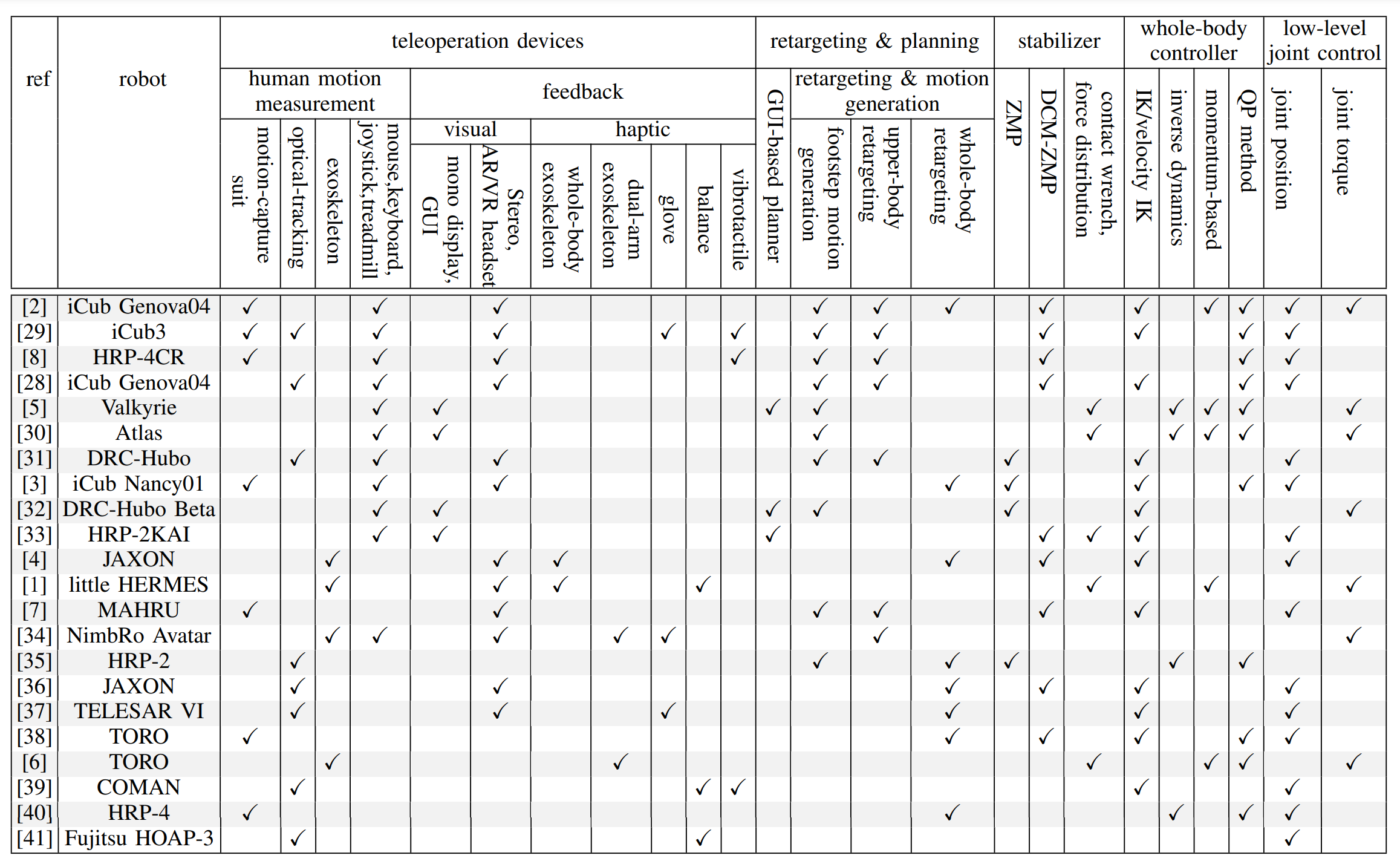

In this section, we provide a detailed description of the technologies available to sense various human states, including the advances to measure the human motion, the physiological states, and the interaction forces with the environment. We report in TABLE 1 the various measurement devices adopted so far for humanoid robot teleoperation.

1) Human kinematics and dynamics measurements

To provide the references for the robot motion, we need to sense human intentions.

For simple teleoperation cases, the measurements may be granted through simple interfaces such as keyboard, mouse, or joystick commands

Different technologies have been employed in the literature to measure the motion of the main human limbs, such as legs, torso, arms, head, and hands.

An ubiquitous option are the Inertial Measurement Unit (IMU)-based wearable technologies. In this context,

two cases are possible,

a segregated set of IMU sensors are used throughout the body to measure the human motion

or an integrated network of sensors is used throughout the human body

Optical sensors are another technology used to capture the human motion, with active and passive variants. In the active case, the reflection of the pattern is sensed by the optical sensors. Some of the employed technologies include depth sensors and optical motion capture systems. In the case of passive sensors, RGB monocular cameras (regular cameras) or binocular cameras (stereo cameras) are used to track the human motions. Thanks to the optical sensors, a skeleton of the human body is generated and tracked in 2-D or 3-D Cartesian space. The main problems with these methods are the occlusion and the low portability of the setup.

To track the users’ motion in bilateral teleoperation scenarios, exoskeletons are often used.

In this case, the exoskeleton model and the encoder data are fed to the forward kinematics to estimate the human link’s poses and velocities

The previously introduced technologies can be used to measure the human gait information with locomotion analysis.

Conventional or omnidirectional treadmills are employed in the literature for this purpose

2) Human physiological measurements

Among the different sensors available to measure human physiological activities, we briefly describe those that have been mostly used in teleoperation and robotics literature.

An electromyography (EMG) sensor provides a measure of the muscle activity, i.e., contraction, in response to the neural stimulation action potential

for estimation of the human effort and muscle forces

Electroencephalography (EEG) sensors can be employed to identify the user mental state. They are most widely used in non-invasive brain-machine interface (BMI) and they monitor the brainwaves resulting from the neural activity of the brain.

The measurement is done by placing several electrodes on the scalp and measuring the small electrical signal fluctuations

C. Feedback Interfaces: Robot to Human

A crucial point in robot teleoperation is to sufficiently inform the human operator of the states of the robot and its work site, so that she/he can comprehend the situation or feel physically present at the site, producing effective robot behaviors. TABLE 1 summarizes the different feedback devices that have been adopted for humanoid teleoperation.

1) Visual feedback

A conventional way to provide situation awareness to the human operator is through visual feedback. Visual information allows the user to localize themselves and other humans or objects in the remote environment.

Graphical User Interfaces (GUIs) were widely used by the teams participating at the DRC to remotely pilot their robots through the competition tasks

An alternative way to give visual feedback to the human operator is through VR headsets, connected to the robot cameras.

Although this has been demonstrated to be effective in several robotic experiments

2) Haptic feedback

Visual feedback is not often sufficient for many real-world applications, especially those involving power manipulation (with high forces) or interaction with other human subjects, where the dynamics of the robot, the contact forces with the environment, and the human-robot interaction forces are of crucial importance. In such scenarios also the haptic feedback is required to exploit the human operator’s motor skills in order to augment the robot performance.

There are different technologies available in the literature to provide haptic feedback to the human. Force feedback, tactile and vibro-tactile feedback are the most used in teleoperation scenarios.

The interface providing kinesthetic force feedback can be similar to an exoskeleton

To convey the sense of touch, tactile displays have been adopted in the literature

All these types of haptic feedback are combined in the telexistence system TELESAR V

3) Balance feedback

Haptic feedback can also be used to transmit to the operator a sense of the robot’s balance.

The idea behind the balance feedback is to transfer to the operator the information about the effect of disturbances over the robot dynamics or stability instead of directly mapping to the human the disturbance forces applied to the robot.

In

4) Auditory feedback

Auditory feedback is another means of communication. It is mainly provided to the user through headphones, single or multiple speakers. Auditory information can be used for different purposes: to enable the user to communicate with others in the remote environment through the robot, to increase the user situational awareness, to localize the sound source by using several microphones, or to detect the collision of the robot links with the environment. The user and the teleoperated robot may also communicate through the audio channel; e.g., for state transitions.

D. Graphical User Interfaces (GUIs)

GUIs are used in the literature to provide both feedback to the user and give commands to the robot.

In the DRC, operators were able to supervise the task execution through a task panel, using manual interfaces in case they needed to make corrections.

The main window consisted of a 2D and 3D visualization environment, the robot’s current and goal states, motion plans, together with other perception sensor data such as hardware driver status

A common approach adopted by the different teams was to guide the robot perception algorithms to fit the object models to the point cloud, used to estimate the 3D pose of objects of interest in the environment. For example, operators were annotating search regions by clicking on displayed camera images or by clicking on 3D positions in the point cloud.

Following that, markers were used to identify the goal pose of the robot arm end effectors

GUIs have also been used to command frequent high-level tasks to the robot by encoding them as state machines or as task sequences